R8 Optimization: Null Data Flow Analysis (Part 1)

18 December 2018

Note: This post is part of a series on D8 and R8, Android’s new dexer and optimizer, respectively. For an intro to D8 read “Android’s Java 8 support”. For an intro to R8 read “R8 Optimization: Staticization”.

The last post in this series was the first to cover R8 and one of its optimizations. This post will cover an optimization which performs data flow analysis of nullability. Let’s dig in!

A coalesce function returns the first non-null argument that is provided. Running the following example, unsurprisingly, prints “one” and then “two”.

fun <T : Any> coalesce(a: T?, b: T?): T? = a ?: b

fun main(vararg args: String) {

println(coalesce("one", "two"))

println(coalesce(null, "two"))

}

R8 and ProGuard will both perform function inlining when a function is small or if it’s only called in one place. Since coalesce is small, its body will be inlined to every call site to be equivalent to the following source.

fun main(vararg args: String) {

println("one" ?: "two")

println(null ?: "two")

}

Were this actual source, the Kotlin compiler will determine that both of the elvis operators (?:) can be determined at compile-time. Compiling and dexing that fake source produces two calls to println with “one” and “two” and zero conditionals.

[000180] NullsKt.main:([Ljava/lang/String;)V

0000: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0002: const-string v0, "one"

0004: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

0007: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0009: const-string v0, "two"

000b: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

000e: return-void

But since the inlining occurs inside of R8 and not prior to running the Kotlin compiler, the actual Dalvik bytecode contains the conditionals.

[000144] NullsKt.main:([Ljava/lang/String;)V

0000: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0002: const-string v0, "one"

0004: if-nez v0, 0006

0006: const-string v0, "two"

0008: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

000b: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

000d: const/4 v0, #int 0

000f: if-nez v0, 0010

0010: const-string v0, "two"

0012: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

0015: return-void

Note how bytecode index 0002 load the string “one” and then index 0004 performs a non-null check that will always succeed. This makes index 0006 which loads “two” dead code. Similarly, index 000d loads 0 (which represents null) and then index 000f does a non-null check that will always fail and fall through into index 0010.

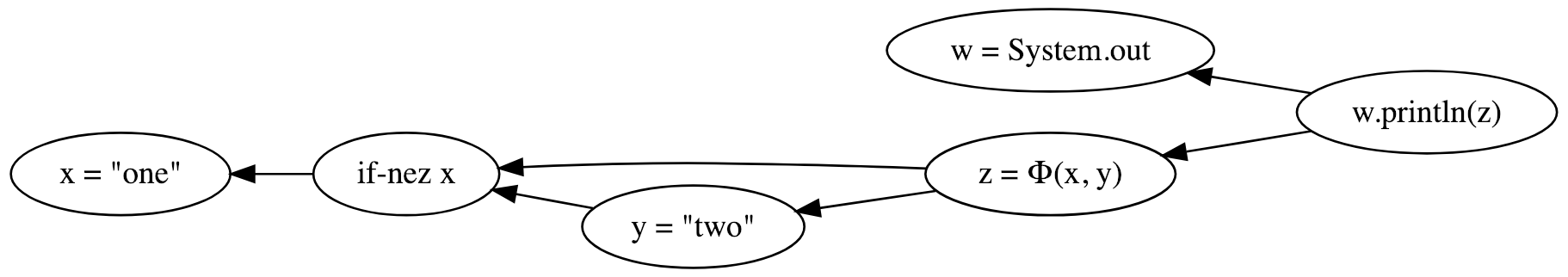

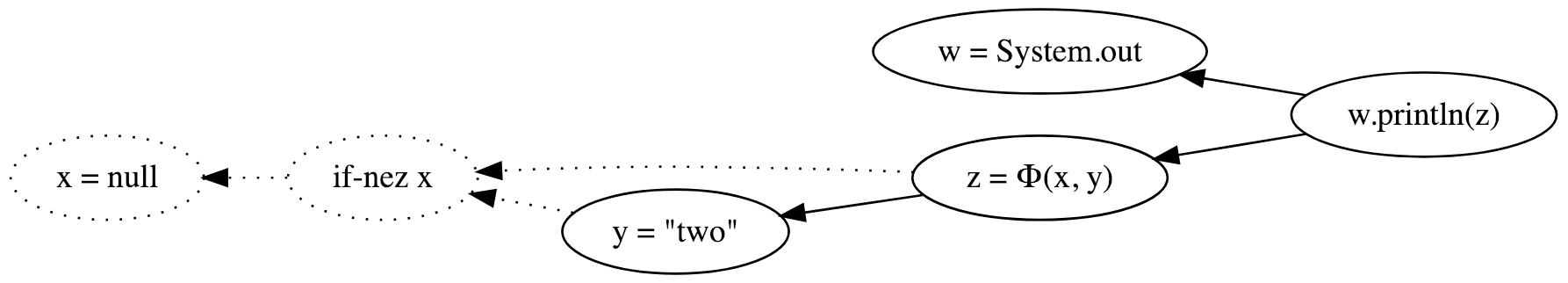

As mentioned in the previous post, R8 uses an intermediate representation (IR) for code. This IR uses static single assignment form (SSA) in order to facilitate certain optimizations. With SSA, R8 can determine how data flows through the program. For the value that flows into the first println after inlining its SSA graph looks a bit like the following.

The foundational property of SSA is that each variable is only assigned once. This is why “two” is assigned to y instead of overwriting x. z uses a special phi function (Φ) to select between x or y based on which branch was taken. As you can see in the previous bytecode output, x, y, and z all wind up becoming register v0 which does get overwritten–single assignment is only for the IR!

If we take the above graph and add nullability information to it, both x and y would be marked as non-nullable since they are both initialized with a constant. As a result, z would also be non-nullable. Since w is a field lookup of a reference, it is potentially nullable.

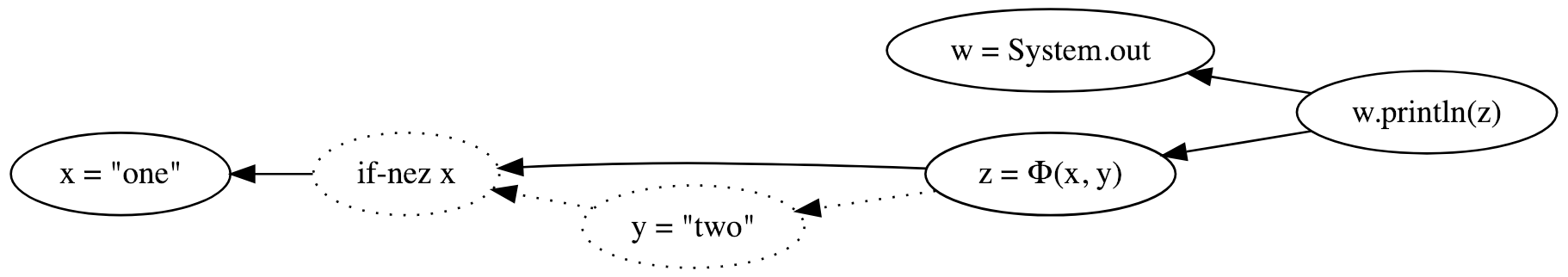

With x being non-nullable, R8 determines that the if-nez bytecode which checks if x is non-null will always be true and thus is useless. The false branch of the conditional which assigns y will never be taken and so it is also useless.

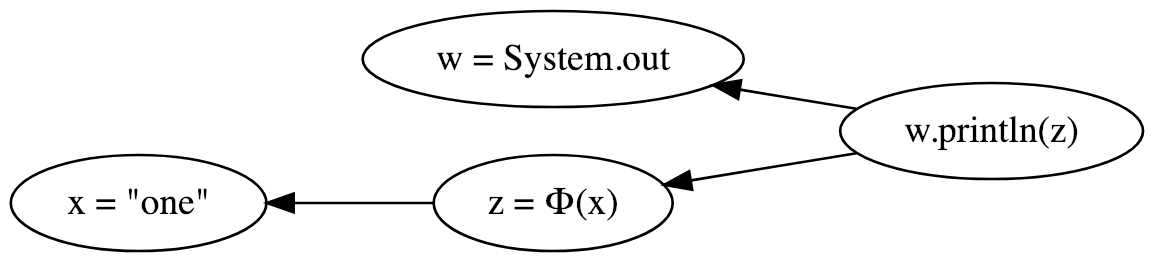

These useless bytecodes can then be pruned from the graph since we know that they are dead code.

z is now a phi function on a single variable, x, which means we can just replace all usages z directly with x.

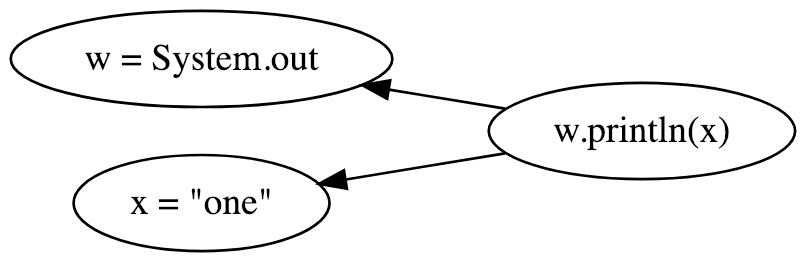

What’s left is just the System.out lookup into w, assignment of the “one” constant into x, and then the call to println on w with the value x.

The above was only the SSA graph which flows into the first println. The second println is the inverse case where the value is initialized to null, a null check is performed, and then a fallback value is conditionally set.

With the SSA IR, R8 is able to determine that both conditionals are useless after the inlining of coalesce and remove the dead branches.

$ kotlinc *.kt

$ cat rules.txt

-keepclasseswithmembers class * {

public static void main(java.lang.String[]);

}

-dontobfuscate

$ java -jar r8.jar \

--lib $ANDROID_HOME/platforms/android-28/android.jar \

--release \

--output . \

--pg-conf rules.txt \

*.class kotlin-stdlib-1.3.11.jar

$ $ANDROID_HOME/build-tools/28.0.3/dexdump -d classes.dex

[000340] NullsKt.main:([Ljava/lang/String;)V

0000: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0002: const-string v0, "one"

0004: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

0007: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0009: const-string v0, "two"

000b: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

000e: return-void

The final Dalvik bytecode now matches that which the manually-inlined source file above produced.

Analysis Inside D8

In attempting to create the bytecode that would be generated after inlining but before nullability analysis eliminated dead code I tried to use equivalent Java.

class Nulls {

public static void main(String... args) {

Object first = "one";

if (first == null) {

first = "two";

}

System.out.println(first);

Object second = null;

if (second == null) {

second = "two";

}

System.out.println(second);

}

}

When you compile, dex with D8, and dump the bytecode from this example, though, the conditionals are still eliminated.

$ javac *.java

$ java -jar d8.jar \

--lib $ANDROID_HOME/platforms/android-28/android.jar \

--release \

--output . \

*.class

$ $ANDROID_HOME/build-tools/28.0.3/dexdump -d classes.dex

[000224] Nulls.main:([Ljava/lang/String;)V

0000: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0002: const-string v0, "one"

0004: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

0007: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0009: const-string v0, "two"

000b: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

000e: return-void

The reason that this happens is because the same IR is used by D8 and the nullability information is still present. Even without doing any of R8 optimizations, when conditionals are present in the IR that are trivially determined to be always true or always false then dead code elimination can occur.

If you use the legacy dx tool whose IR does not contain this information the bytecode will retain the conditionals and dead code.

$ $ANDROID_HOME/build-tools/28.0.3/dx --dex --output=classes.dex *.class

$ $ANDROID_HOME/build-tools/28.0.3/dexdump -d classes.dex

[000204] Nulls.main:([Ljava/lang/String;)V

0000: const-string v0, "one"

0002: if-nez v0, 0006

0004: const-string v0, "two"

0006: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0008: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

000b: const/4 v0, #int 0

000c: if-nez v0, 0010

000e: const-string v0, "two"

0010: sget-object v1, Ljava/lang/System;.out:Ljava/io/PrintStream;

0012: invoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Ljava/io/PrintStream;.println:(Ljava/lang/Object;)V

0015: return-void

So while the data flow analysis really shines when optimizations like inlining are being applied by R8, if constant conditionals and dead code are present directly from source they’ll still be eliminated by D8.

This post only scratches the surface of the data flow analysis inside R8. The next post will continue to expand on the nullability analysis with respect to how Kotlin enforces nullability constraints at runtime.

(This post was adapted from a part of my Digging into D8 and R8 talk. Watch the video and look out for future blog posts for more content like this.)

— Jake Wharton